Time-travelling: preserving pasts and presents for futures

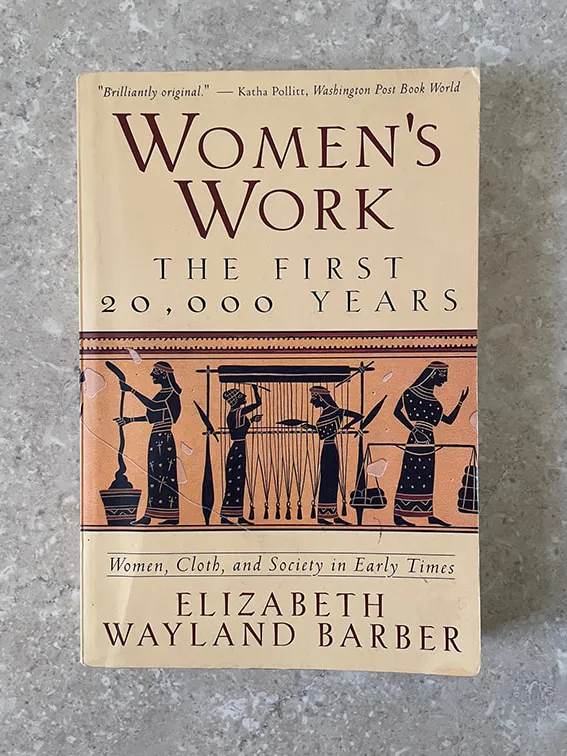

Textiles and domestic artefacts survive as records of events, lives, patterns, cultural and technical knowledge that might otherwise be lost. Lives can be recorded from intimate and individual perspectives but can also record the global news, survival strategies and cultural phenomena, carrying this into the future.

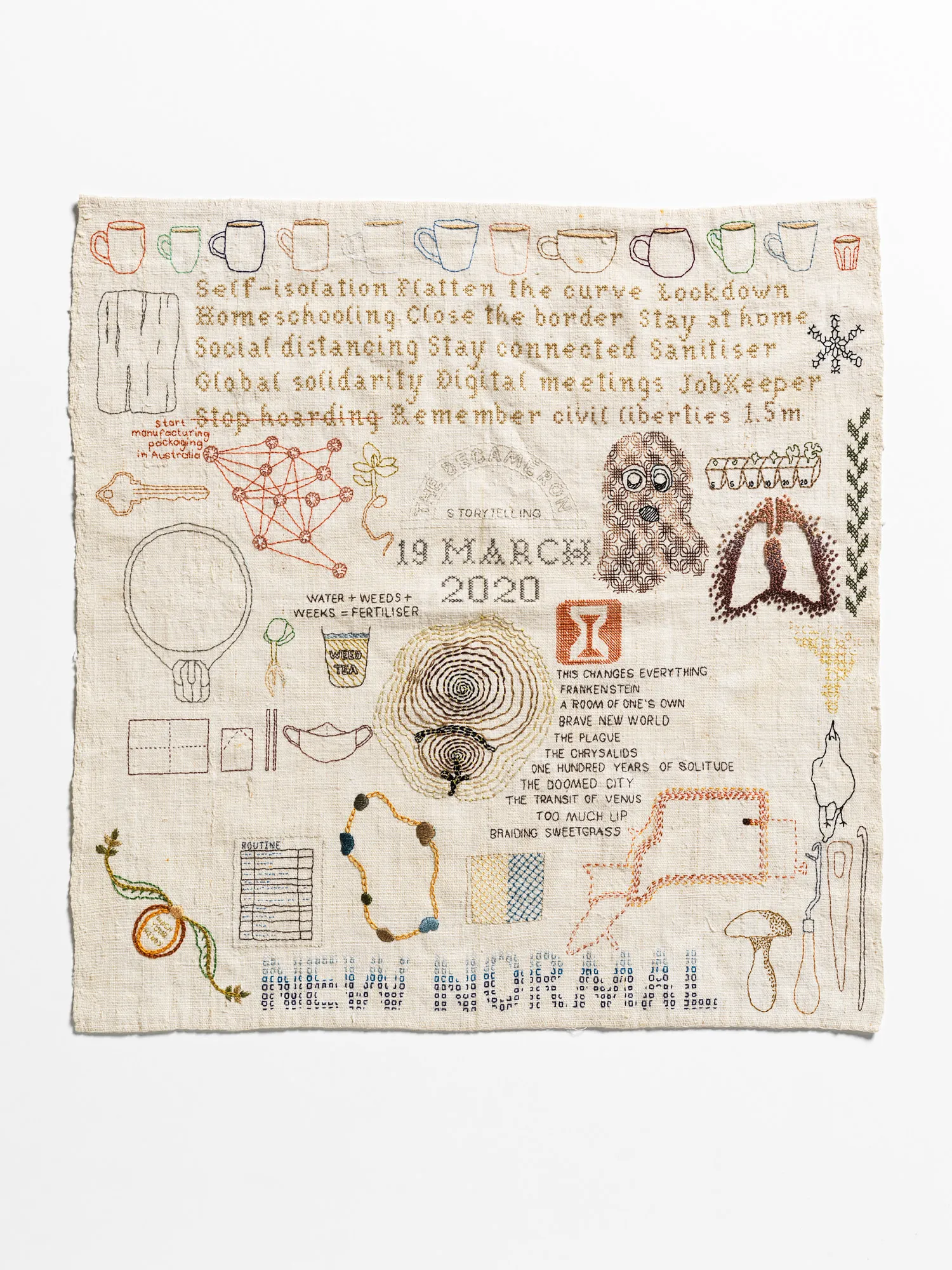

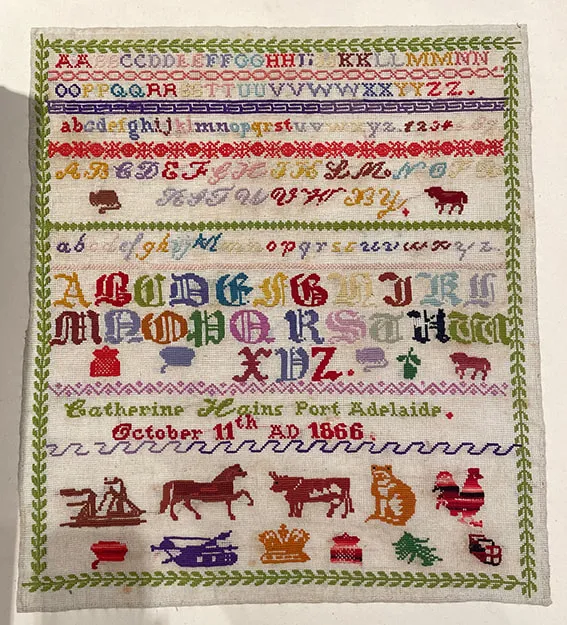

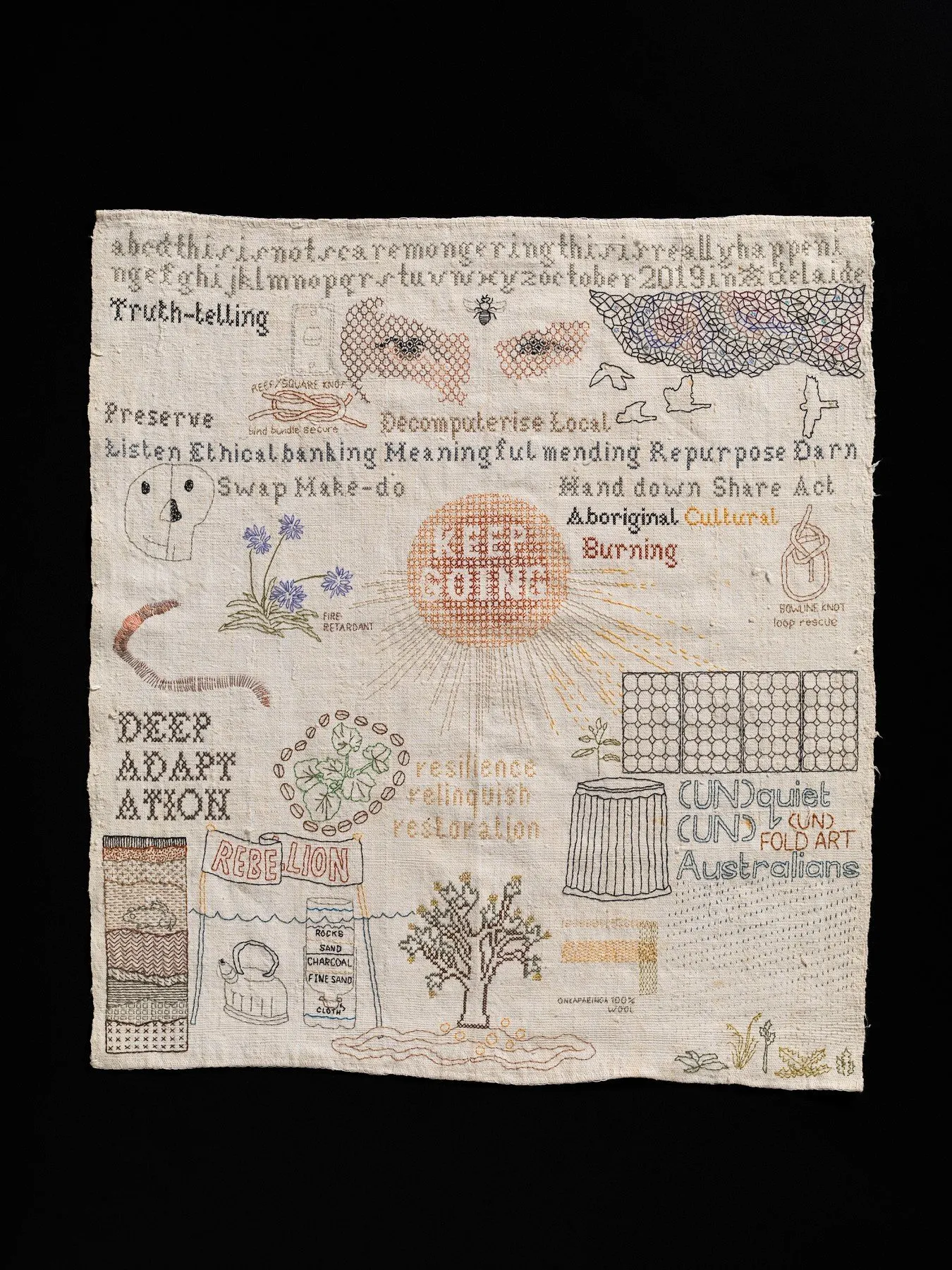

Sera Waters, Survivalist Sampler #2, 2020-2021

Photograph Grant Hancock

Sampling: a tradition for the future

Before samplers became associated with ‘feminising’ and ‘educating’ girls, the ancient practice of ‘sampling’ had been used for centuries as a way of collecting and passing along patterns, skills and knowledge. Today, numerous historic samplers have outlived their makers by centuries, remaining as records of individual lived experiences, values and beliefs, and patterns otherwise lost to time. I have been rethinking sampling as a method toward survival. How can sampling be used to not only record the events of now, but preserve information that could potentially be lost?

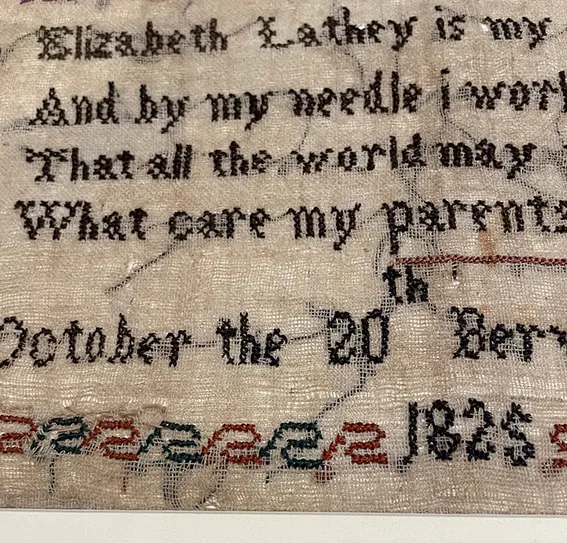

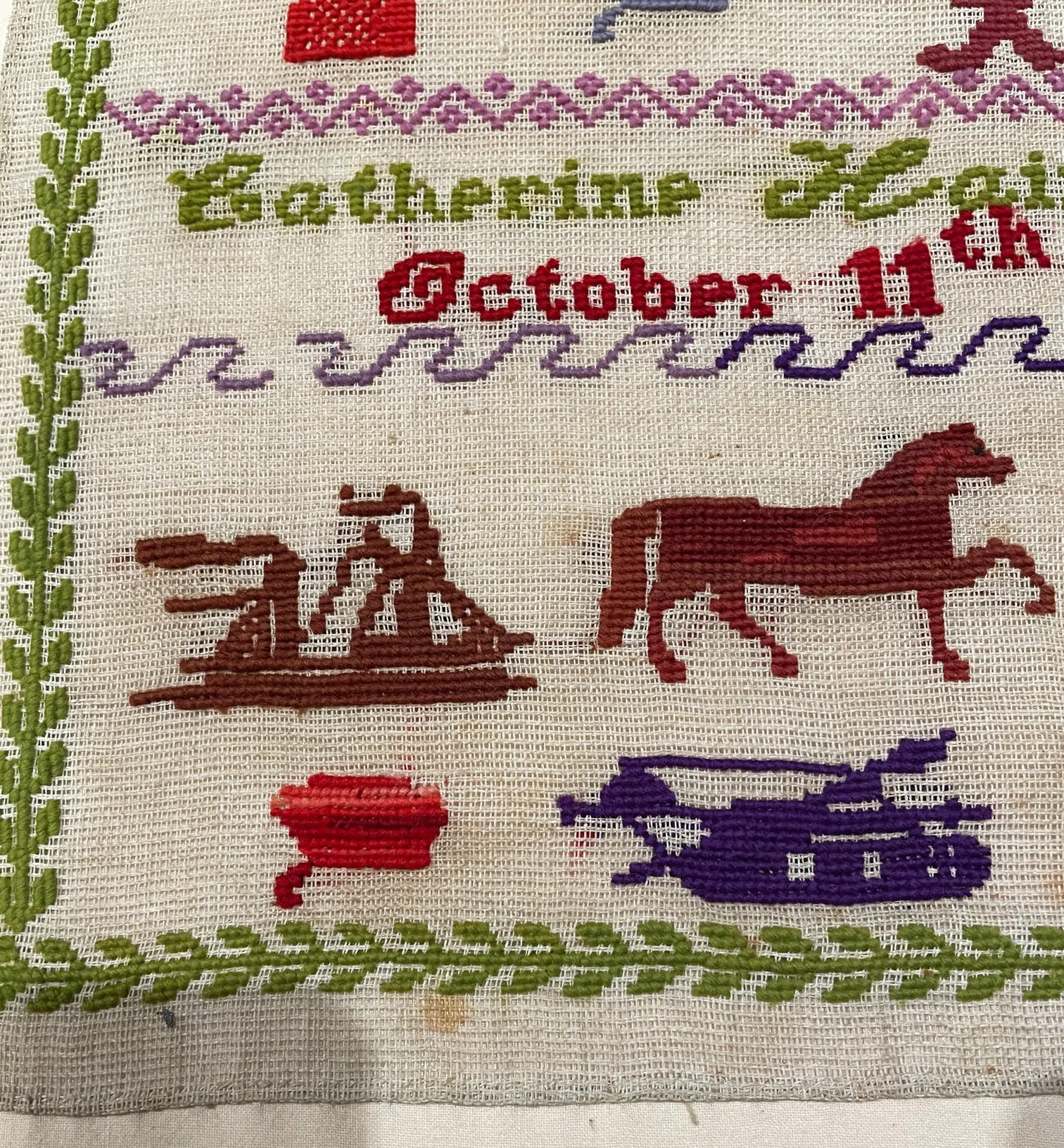

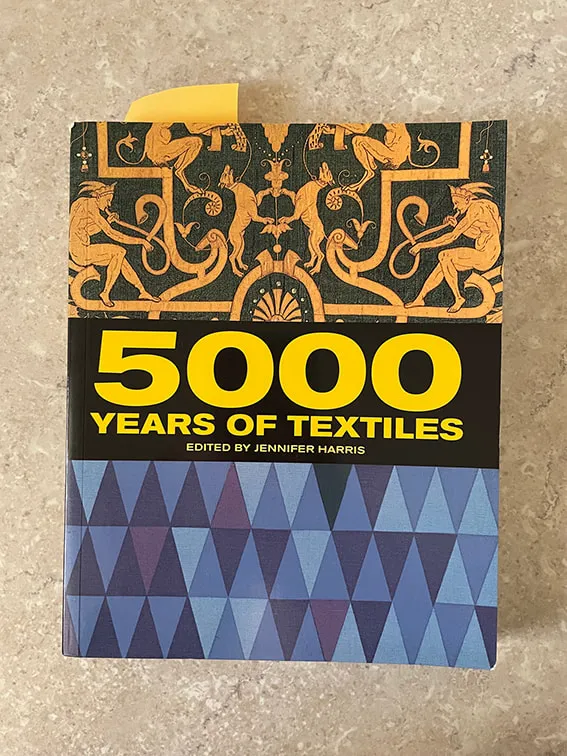

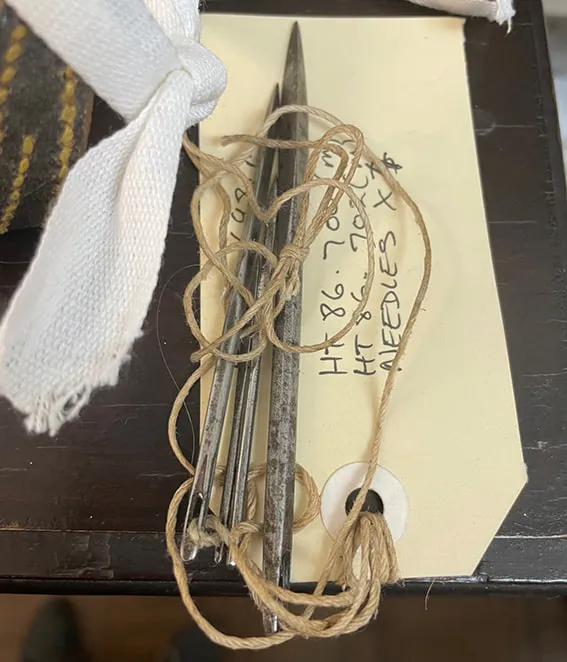

Sampler Artefacts

Photographs of items in the Art Gallery of South Australia collection: with thanks to Rebecca Evans.

Survivalist Samplers

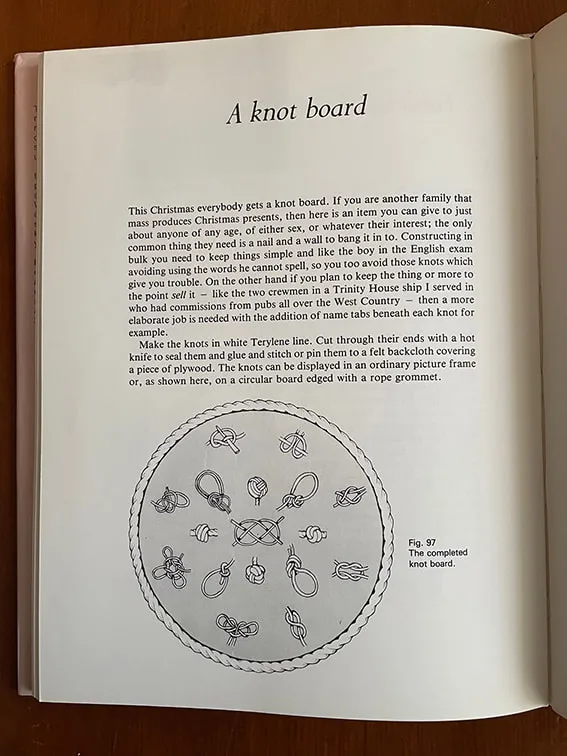

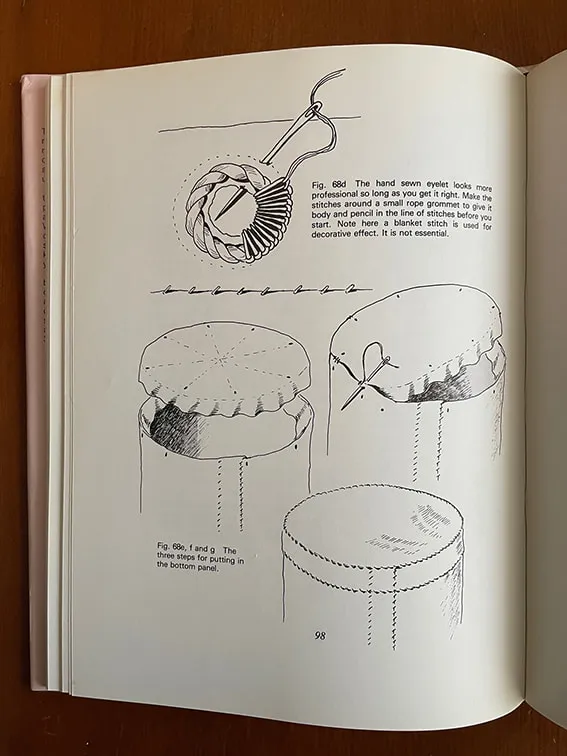

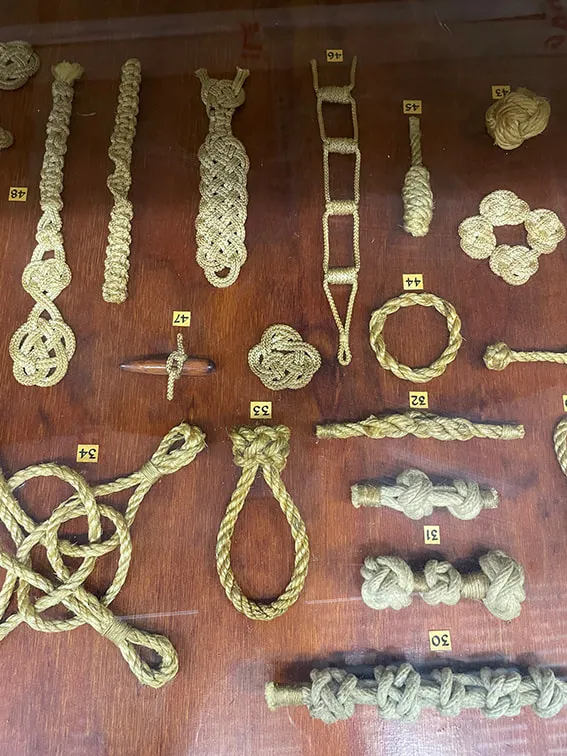

In 2019 I began the Survivalist Sampler series, an ongoing series using ‘sampling’ as a way to combat the loss of important survival knowledge and simultaneously process the influx of copious amounts of information. Survivalist samplers gather survival-related information from family traditions, conversations, local ecologies, news, shared skills and research, and use the slow method of stitch to store this in a non-digitised mode. Precedence, for me, is given to preserving hand-made textile techniques, ranging from diagrams of knots, embroidery styles, or small examples of darning for mending worn-out clothing.

The initial Survivalist Sampler, stitched in a ‘spot sampler’ style (rather than band sampler), gathered together useful pragmatic and psychological information which began with a focus upon climate change which was exacerbated greatly with the major 2019/2020 Australian bushfires. Stitching ranged from diagrams of solar panels, terms such as ‘decomputerize’ and ‘Aboriginal Cultural Burning’, to depictions of agapanthus which act as a fire retardant in bushfires.

#survivalistsampler project

Patrick McDonald, 'A Stitch in Time', SA Weekend, The Advertiser, June 26-27 (A review of a selection of Survivalist Samplers exhibited as part of the #survivalistsampler project in Embroidery: Oppression to Expression, David Roche Foundation, 17 June - 25 September 2021).

From March 2020, propelled by the pandemic, the Survivalist Sampler series transformed into a collective and community-based project on Instagram using #survivalistsampler. Individuals nationally and internationally, notably all women, responded; they posted their progress and reflections to create a community driven project online. Made in real-time and borne of the pandemic, their samplers emerged in response to challenges being faced, charting events and information as it unfolded. Since this time there have been workshops, online and in person, a book chapter, two exhibitions and the uptake of ‘sampling’ across multiple mediums as both a way to exorcise and record people’s personal experiences during this pandemic, and as a way to head into the future differently armed with information, records and hope.

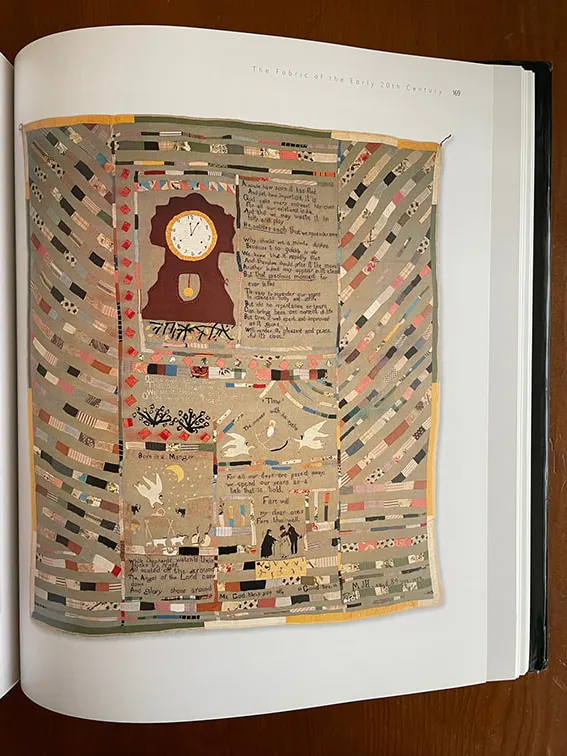

Intergenerational Selves

Domestic textiles, often grouped under categories such as hand-craft, folk art, or popular art, hold in their fabric and stitches intergenerational links. As writer on Folk art, Jim Logan has observed ‘many women feel a strong sense of connection to their forebears through the traditions of embroidery and quilting’ (Logan. P. 6). What we inherit and learn from our mothers or grandmothers, aunts or grandfathers, are actions and materials that link us to our ‘intergenerational self’, that psychologist Marshall Duke says enables not only personal resilience but also, when Duke studied this in children, knowledge ‘they belong to something bigger than themselves’ (Feiler 2013). The intergenerational self, of knowing oneself beyond one lifetime, I would argue is a perspective that acts as a reminder of our responsibilities and living with care.

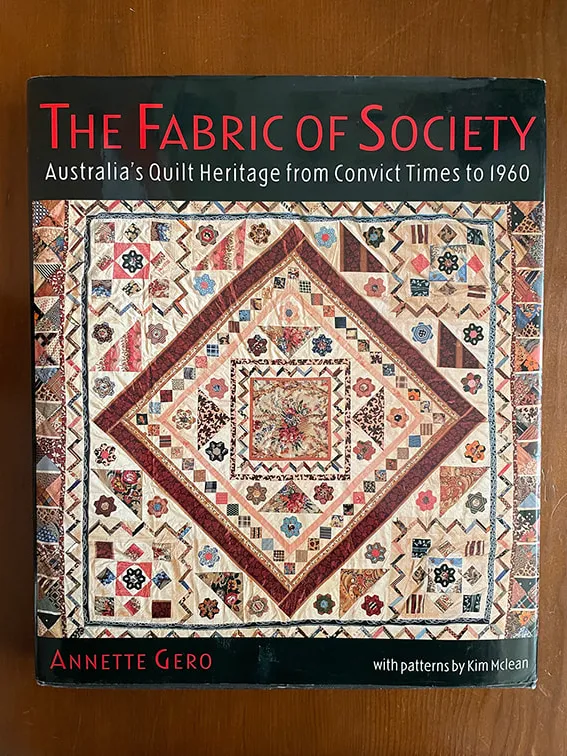

Mary Jane Hannaford, Time, c. 1924 (from The Fabric of Society, Annette Gero)

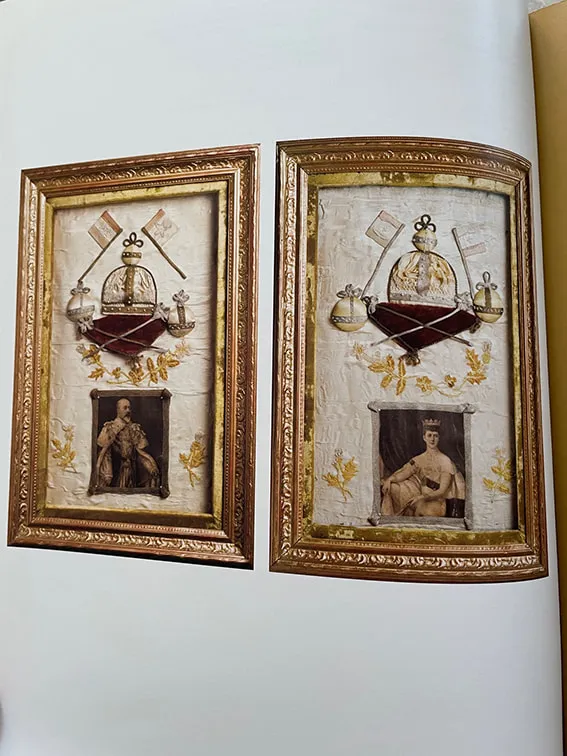

Emma Anders, Pair of patriotic panels depicting King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, c. 1905 (from Queensland Folk Art catalogue, Ipswich Gallery)

Artefacts

This pair of embroideries (in the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia) celebrate the marriage of Alexandra of Denmark and Edward VII and were made by a German immigrant in the Barossa Valley. They demonstrate how embroidery was used by settler colonists; as fashionable home-decoration, to display connections to concurrent European news events, as well as keeping in touch with textile traditions.

Portrait of Alexandra, 1863, Barossa Valley, South Australia, various embroidery threads, painted silk, beads, timber frame, 64.0 x 58.0 cm;

Portrait of Edward VII, 1863, Barossa Valley, South Australia, various embroidery threads, painted silk, beads, timber frame, 64.0 x 58.0 cm;

Photographs of items in the Art Gallery of South Australia collection: with thanks to Rebecca Evans.

Sail-making and the McKay lineage

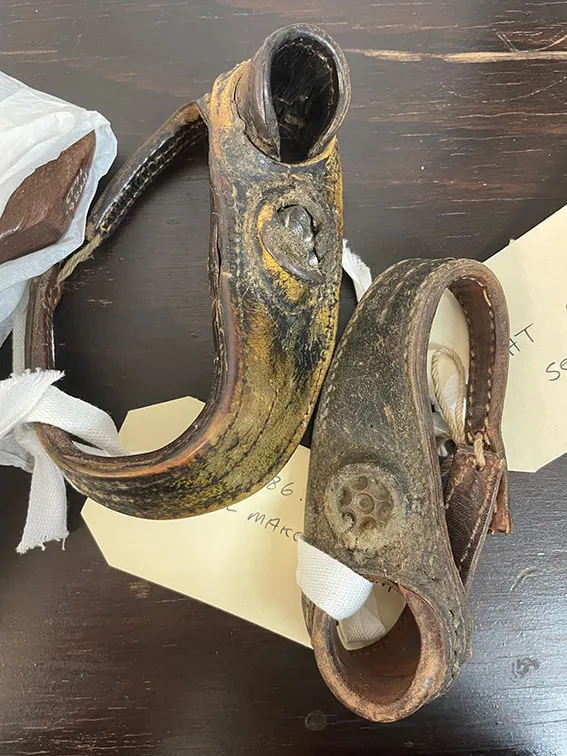

A range of sail-making and ketch related artefacts.

Photographs of items in the South Australia Maritime Museum collection: with thanks to Lindl Lawton.

Sailing Textile Skills Research