Patterns

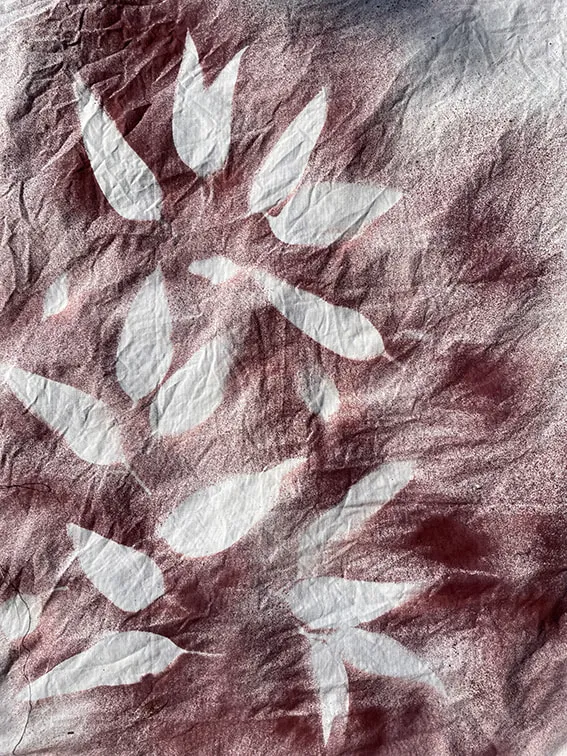

Patterns carry deep ancestral knowledge, reproduced from generation to generation in habits, rituals, family traditions and systems of understanding the world. In an Australian context, a pattern ripe for disruption is the 'geometric discipline' of settler colonialism that has been enacted upon land, bodies and domestic textiles.

Photograph by Sia Duff

Courtesy of Guildhouse

Why patterns?

Patterns are often derided or dismissed as “decorative” but patterns carry age-old ancestral knowledge. Patterns are reproduced from generation to generation; in habits, rituals, family traditions, and more. Intergenerational patterns support and sustain systems of organising and understanding one’s world. In Australia this is particularly important to examine given the passing along of “normalised” colonising behaviours and patterns of home-making over the last two hundred years; patterns often ill-fitted to unceded Aboriginal Country. Colonising patterns are reproduced across daily life, including in textiles where they are embedded in domestic fabrics, home-craft kits, embroidered motifs, gridded patterns and more. In unravelling such patterns I aim to notice, examine and unpick them to acknowledge their embedded knowledge. It is also necessary to rethink many patterns, especially those reinforcing settler colonialism, to expose, unravel, restitch and use these renewed patterns to decolonise and shift us into new patterns for a more survivable, caring and ecologically-minded future.

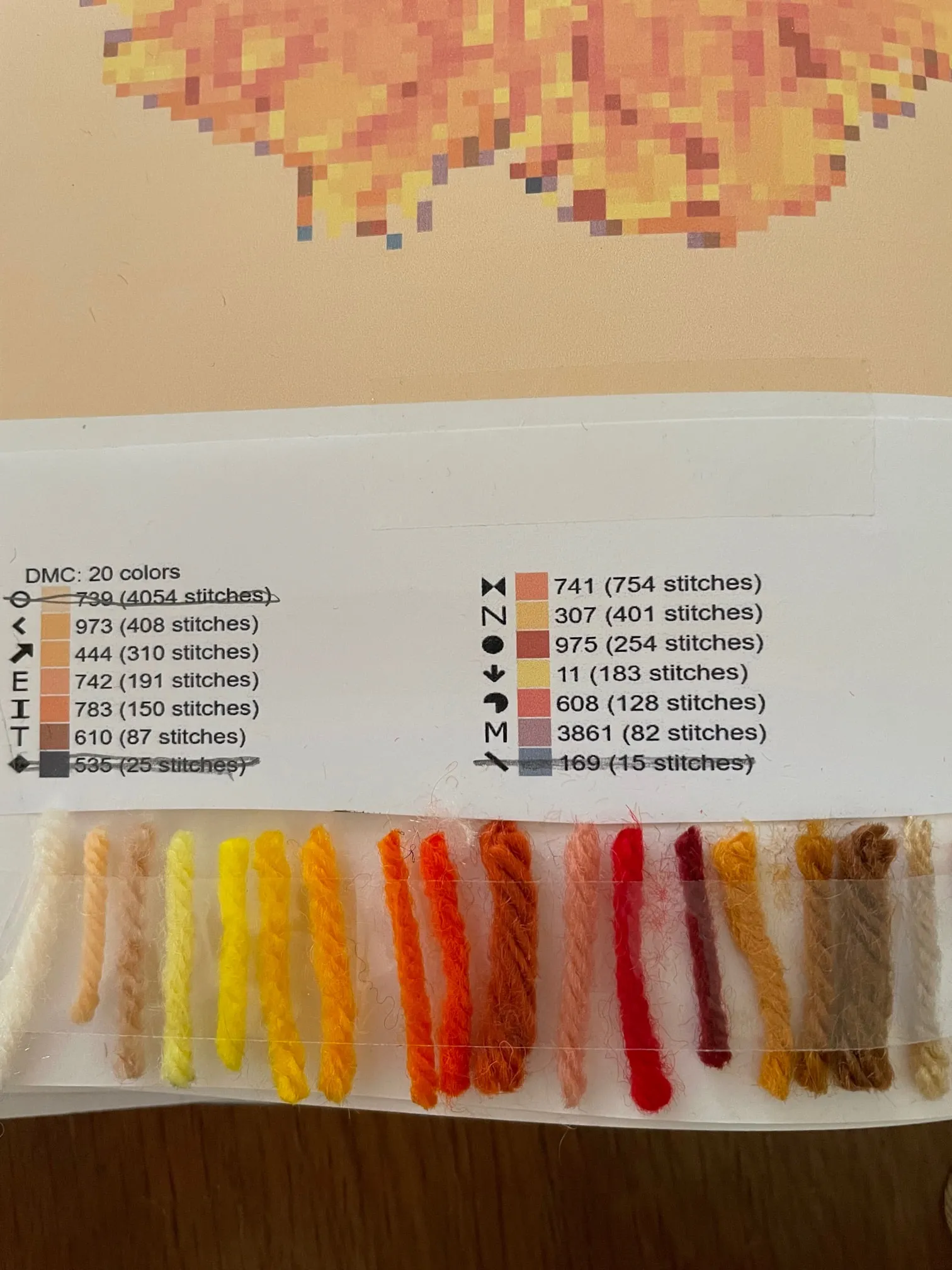

Sunset Shard Mask

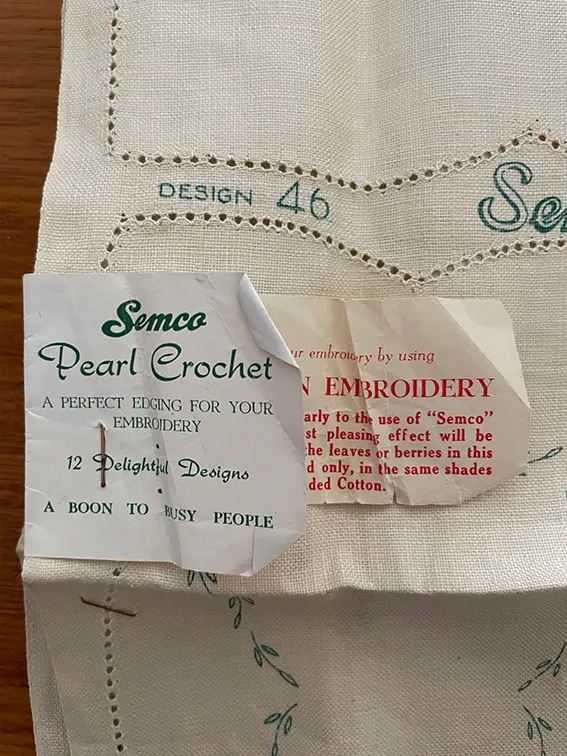

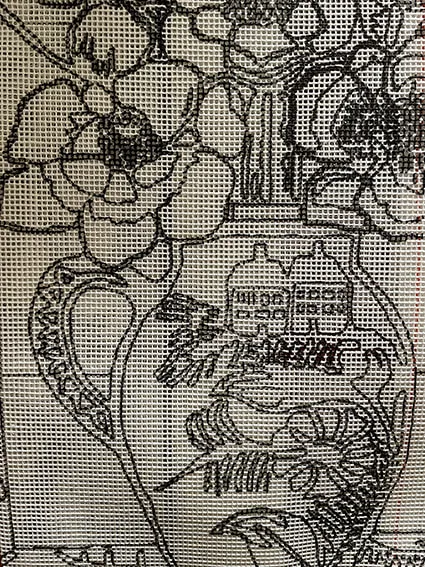

Sunset Shard Mask is an exploration of the sunsets and bushland motifs and patterns that populate the 1980s Semco Longstitch Originals series. The colour-by-number kits, which included a canvas upon which was drawn a landscape pattern and a selection of pastel wool, were designed to create a nostalgic pastoral portal representing a settler colonial mirage of living on the Australian land. As well as creating protection from the harsh Australian sun, this mask, constructed of shards, shatters and put's in one's face the fallacy that is the "Australian landscape”.

‘The dazzling glare of the Australian light necessitates a downward look and an attention to the patterns and rhythms of the ground.’

Barbara Bolt, "Shedding Light for the Matter’, Hypatia 15, no. 2 (Spring) (2000): p. 209

Found kits & Patterns & Research

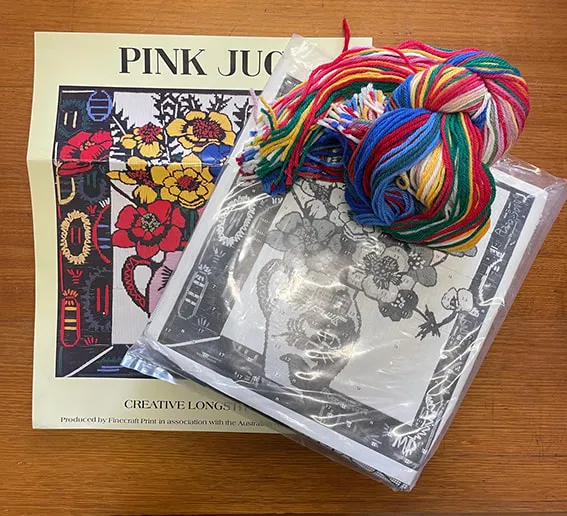

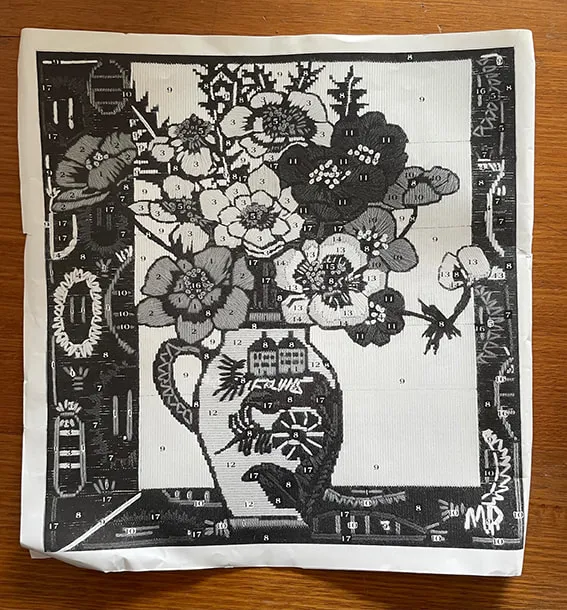

Margaret Preston: Pink Jug kit

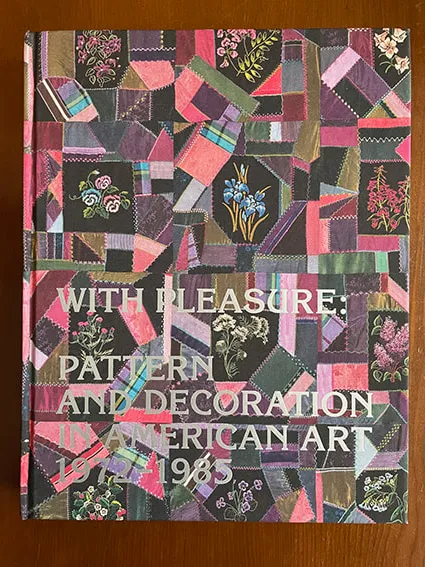

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles with Yale University Press, 2019.

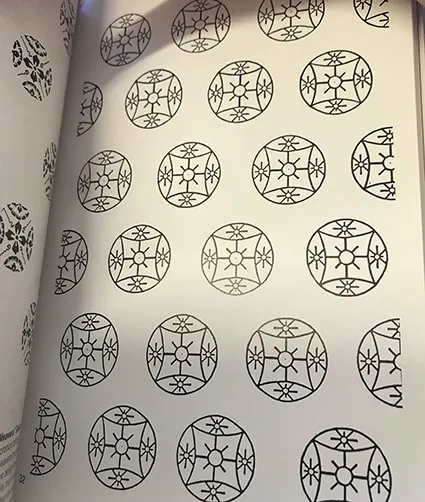

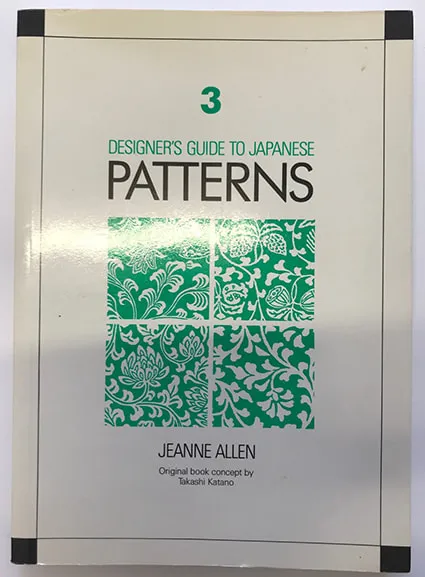

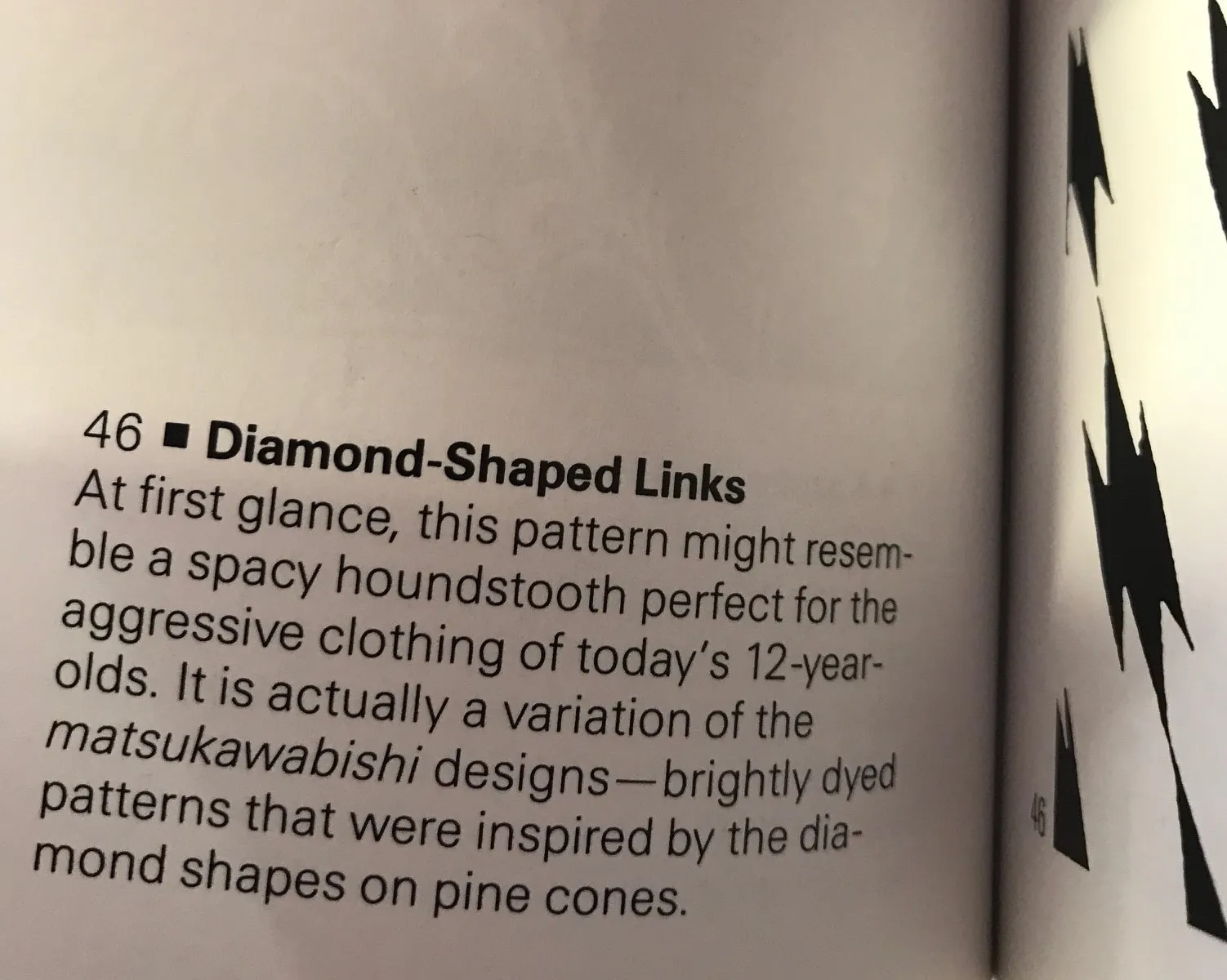

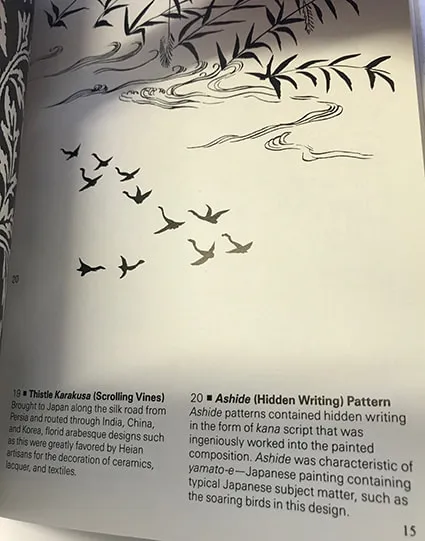

Study of Japanese patterns reveal some pragmatic uses of patterns. This example, of the Hanabashi Weavers’ Guide, is instructional, recording the process of a particularly challenging knot. In the words of Jeanne Allen it ‘is a clever adaptation of the pattern guide used by the weavers to execute the difficult roundels’. Other patterns replicate details from local species, such as pine cones, other patterns spell out words, and many patterns reveal the movement of knowledge across permeable cultural borders.

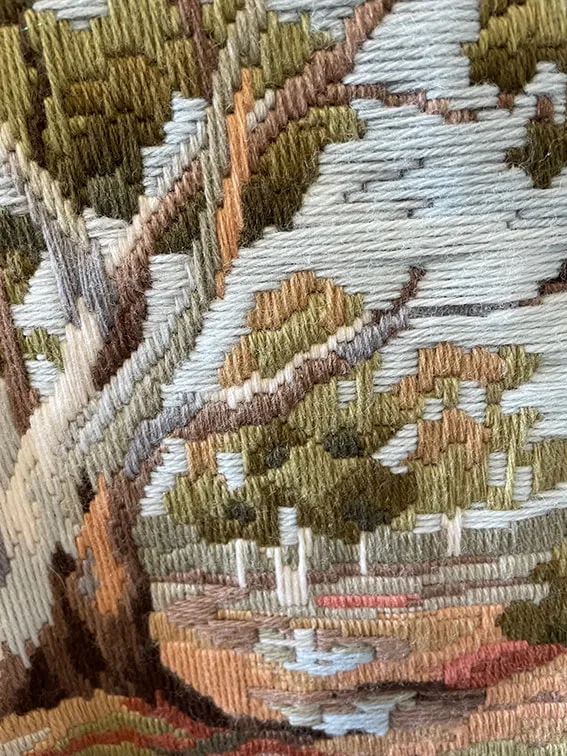

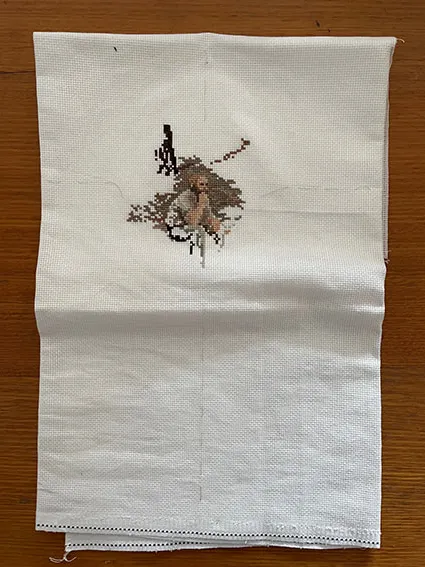

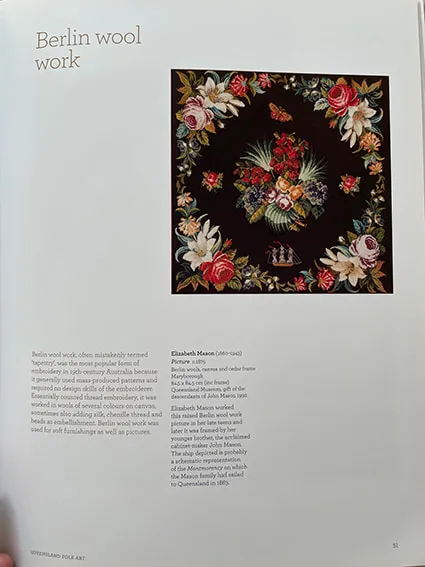

Berlin wool work

Berlin wool work was imported to Australian shores with settler colonists. This form of counted thread embroidery (not 'tapestry' as it is often mistakenly referred to) uses predominantly wool upon canvas and was mass-produced as kits for wall hangings and soft furnishings. Berlin wool work was highly popular in the nineteenth century and often depicted "patterns" consisting of European flowers. The importation of these non-native patterns is another form of colonisation, emanating out from home interiors.

Page from Queensland Folk Art catalogue, Ipswich Art Gallery, 2009.

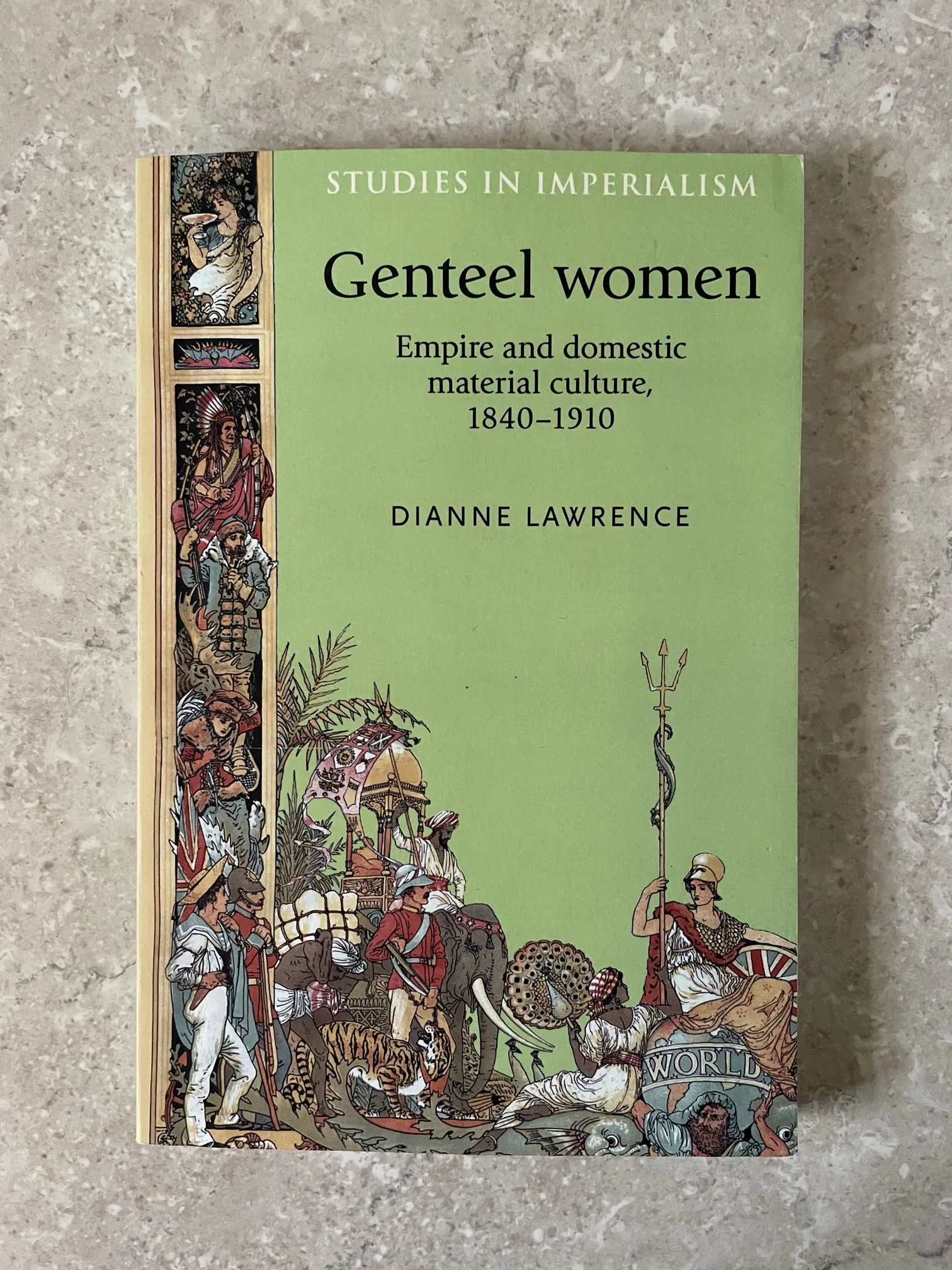

“The presence of flowers in the woman’s throne-room served to showcase another aspect of her femininity, to provide a reminder of the ‘wilderness’ beyond, and hence how she contributed to civilising and taming that world, and how therefore her sphere of influence extended well beyond the enclosure of the living room”

Dianne Lawrence, Genteel Women, Manchester University Press: Manchester, p. 125.

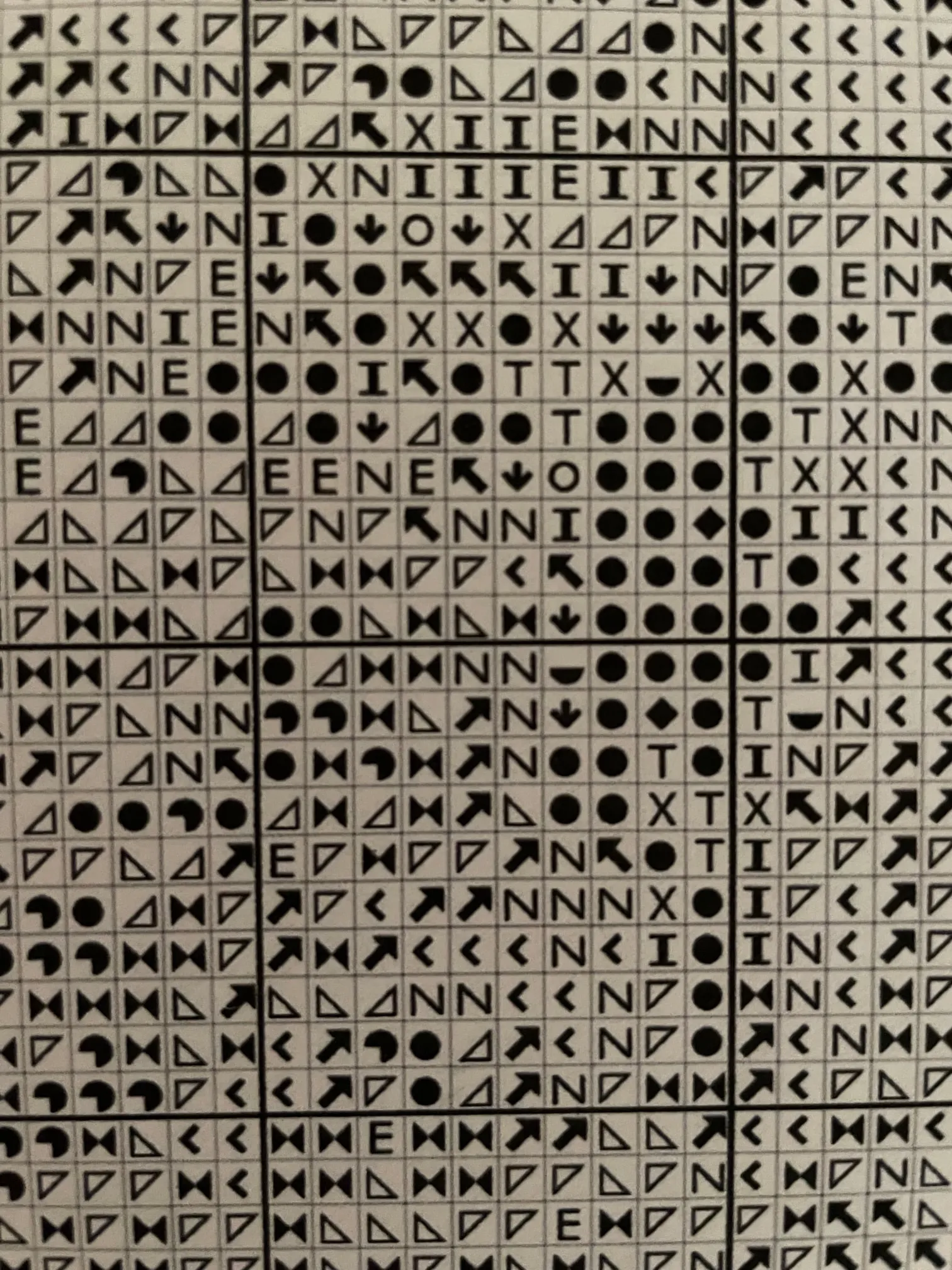

The patterns within a ‘Geometric Discipline’:

The idea of a ‘geometric discipline’ came from reading Denis Byrne’s chapter "Nervous Landscapes: Race and Space in Australia" (in Making Settler Colonial Space: Perspectives on Race, Place and Identity, edited by Tracey Banivanua Mar and Penelope Edmonds, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, pp 103-28.). Byrne investigates the gridding of our lives; homes, school tables, streets, cupboards with boxes within boxes (rooms), and even coffins, forcing a rather unnatural lived experience of walking straight lines, turning ninety degree corners and adhering to rigid and controlled ways of being. This ‘geometric discipline’ has been a pattern of controlling, containing and stifling behaviours replicated across Australia as colonising; putting in fence lines, building angular houses and walls, gardening and monoculture farming in rows, overwriting pathways for bitumised roads. I have evidence of my ancestors replicating these geometric disciplines again and again: one ancestor was even assistant to George Goyder who became Surveyor-General of South Australia in 1861. These angular boundary keeping tendencies have also been inherited through practices of needlework. Counted thread modes of embroidery such as blackwork, Berlin needlework, cross-stitch or long-stitch work upon grids, follow linear boundaries, and are restrained by a repetitive geometric discipline. Only retrospectively have I come to understand all my embroidering practices are bound to grid-like structures, ordered according to squares, and require the body (and mind) to see the world through limited patterns. This grid could be referred to as a ‘spectral structure’ (Lisa Saltzman, Making Memory Matter: Strategies of Remembrance in Contemporary Art. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 51) for often it lurks underneath the layers of labour, but still governs the potential imaginings and physical arrangement of matter on the surface. Rather than move beyond the grid and its requisite geometric discipline my artwork tends to exacerbate these geometric patterned behaviours, often to the point of obsessive diligence. The grid strains to contain the repetitive patterns I stitch again and again to draw attention to their restraints.

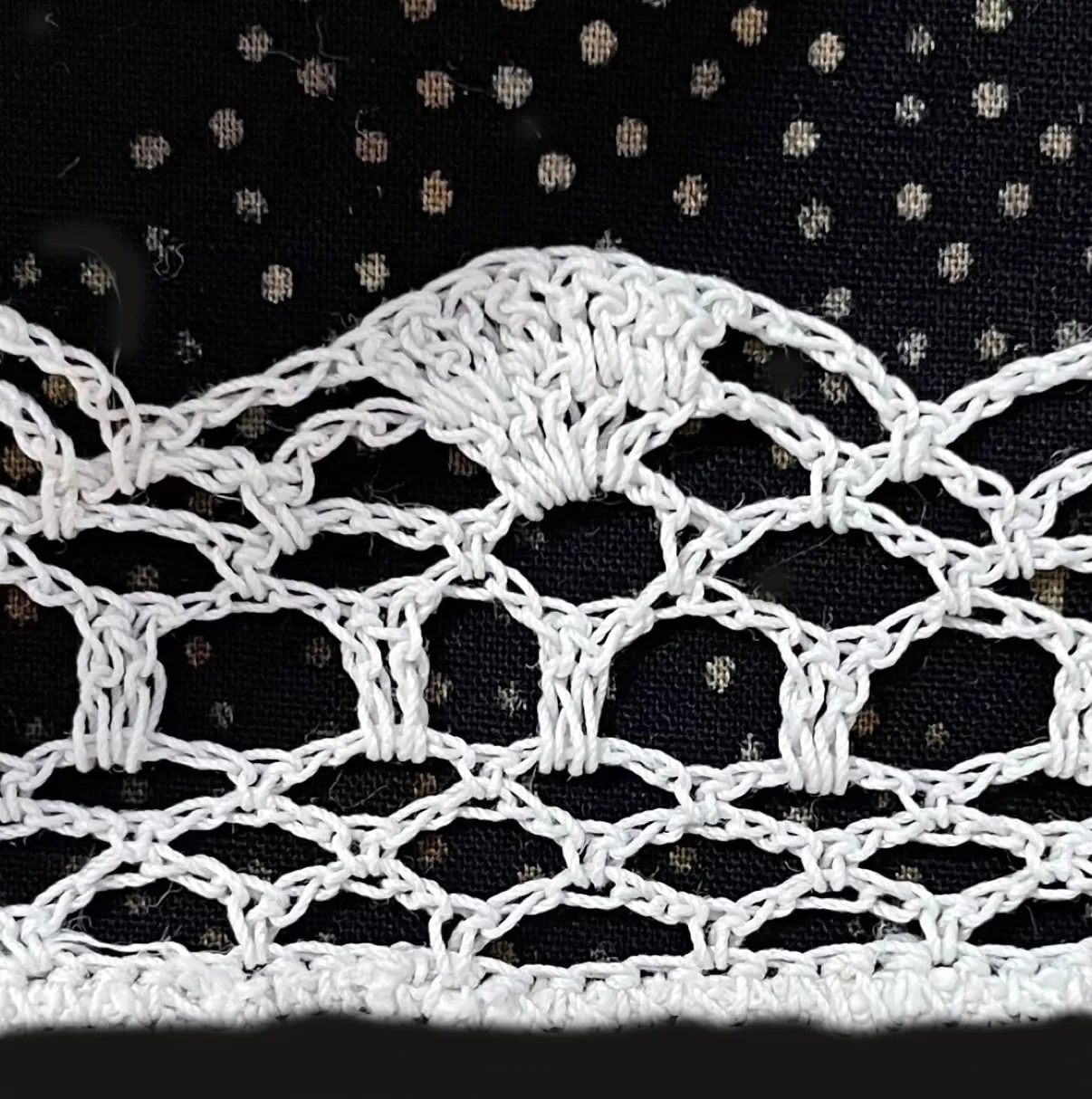

Doily borders

On my daily walk I noticed the shadow of a wire fence. When cast onto the footpath it looked strikingly similar to lace. It struck me that fences, like the crocheted and needleworked borders around doilies, surround an interior with a patterned and decorative outline. Both fences and doilies often incorporate repetitive patterns from 'nature' like ripples, shells or tree trunks, and use flora, plants and bird life, to normalise acts of containment, spatial control and ownership. Borders, large and small, change perceptions of beginnings and endings and inclusions and exclusions.

Doilies have a relatively recent backstory, coming to prominence in the Victorian era, but traced back to a 17th century Draper. Their holey appearance, crocheted, tatted or knitted, is a type of openwork celebrated for being clean and airy. These links with 'cleanliness' carry dubious colonial connotations, and in reality, when the white textiles are submerged all kinds of grime seeps out.

Mostly today we know doilies as outdated decorative protectors; shields for wooden furniture, table tops and nestlers for domestic displays. While researching and playing with my own portable doilies I have been recording symbols/patterns from my generously donated and growing doily collection. Many are floral pattens, others less obvious.

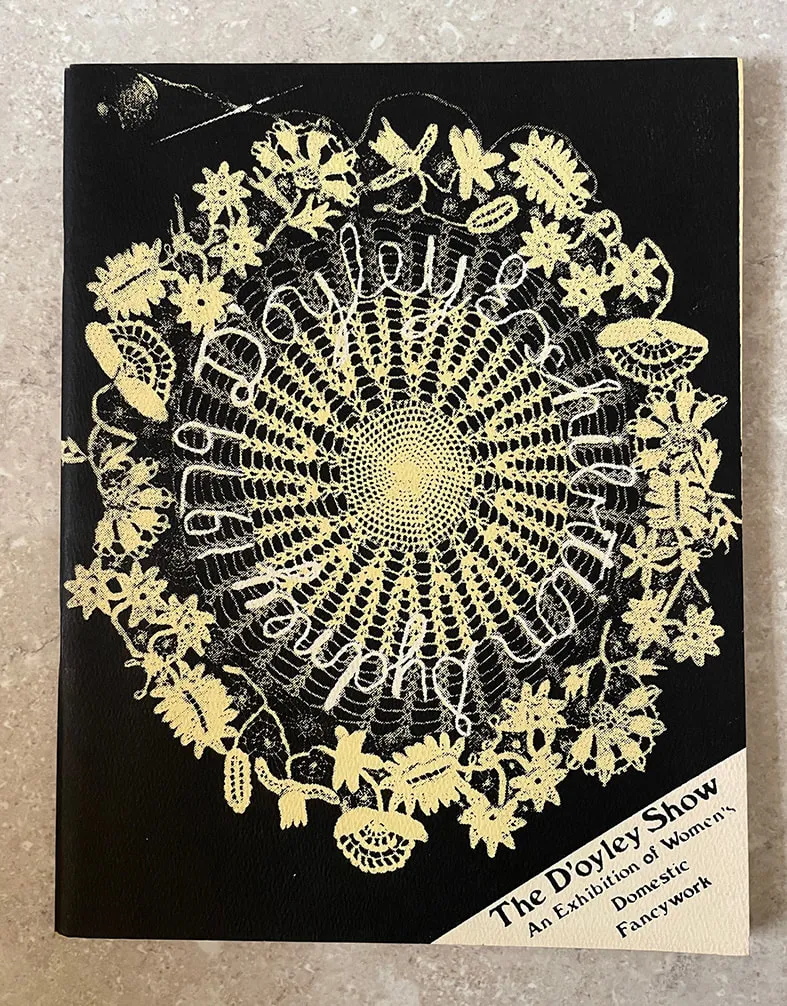

This study responds to The D'oyley Show, a 1979 project carried out by The Womens Domestic Needlework Group. Their catalogue and research notes that 'Because women's work has been historically undervalued, pattern books and needlework have not been collected and therefore very little information, even from recent times, has survived' (p 5.). Their aim was to begin a more thorough recording to give rightful place to these expressions and, in their words, 'a more objective history of women's domestic needlework'.

CODES AND COLOURS