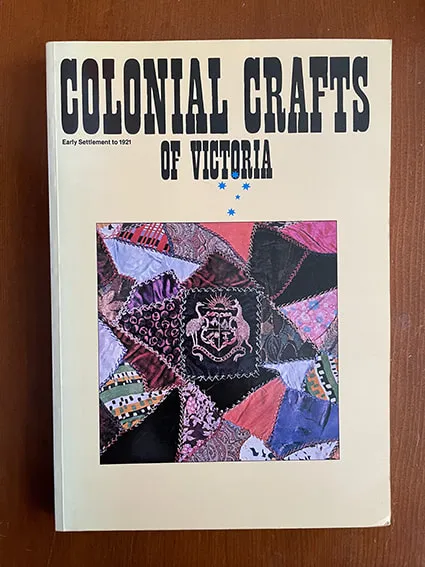

Mass Making-do

Repurposing, reusing and making-do are age-old traditions. Restoring these traditions as a future way forward recognises the value of textiles and addresses the fact they are one of the globe’s main pollutants.

Photograph by Sia Duff

Courtesy of Guildhouse

Repurposing for Planetary Repair

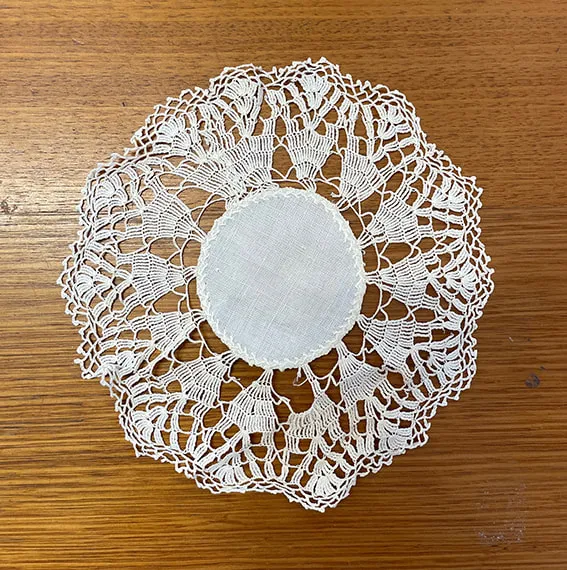

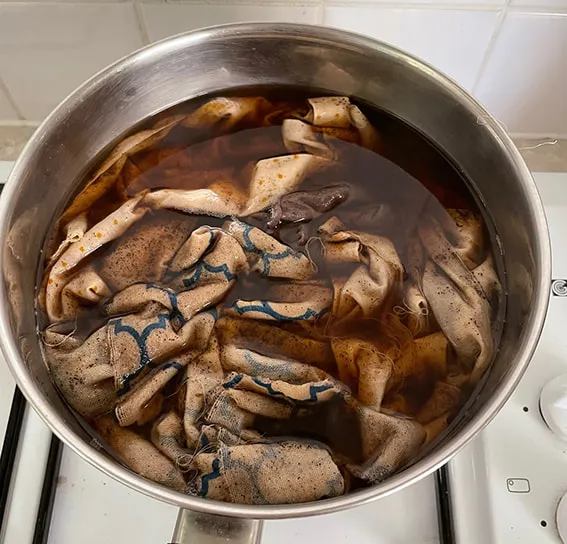

Like our ancestors, what if we were forced to make all of our textiles by-hand or by making-do, using only what can be gathered, found secondhand, repurposed, altered or mended? Repurposing is an old tradition, which when restored, rethinks the life cycle of textiles in its entirety; from initial construction all the way to rags and disintegration. Repurposing especially ponders the great shifts that have occurred in how we value textiles - from once being prized and passed along family lines, to the present-day mass production of fabric by the roll and 'throw-away' behaviours. An aim of mass making-do is to reinstate value by recognising the incredible technologies and skills embedded in textiles, and to keep these in circulation longer through acts of care.

This braided rug was made under the tutelage of artist Ilka White

Care, Collections & Research

Materials, and the material relations they carry along with them (for example life spent in other homes or for other uses) are critical to care. With a gathering force, throughout my practice I have found myself recipient of family textile and domestic material collections; people contact me for example if an elderly family member might be going into care and to gift and find a new carer for a loved collection. These gifts range from trims, fabrics, old sewing boxes, furs, half completed kits and much more. I enter into a transaction when accepting these gifts, to perform material acts of care, to repurpose these materials and acknowledge their past lives while redirecting them toward new narratives. As a result my work uses predominantly pre-loved matter and inherited techniques, especially textiles: stuff and traditions marked by human ingenuity, labour, and soiling, from my own family as well as other people’s. I make with half completed projects, from old kits that are no longer in circulation, from materials intended for other purposes, and merge these association into new narratives and directions.

Folk Art & Making-do for a Changing Future

‘The fundamental concerns of folk art – utility, family, politics, gender roles, work, the natural world and religion – are universal subjects with which all can relate, connections made across time and cultures’.

Jim Logan, ‘Towards a definition of Australian folk art’, in Everyday Art Australian Folk Art, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1998, p. 6.

Folk art, which goes by other names such as popular art or home craft, is a mode of making that, according to artist Jeff McMillan, has its "origin in tradition. It has been passed down and therefore is representative of a collective"1. This collectivity, of being of families, communities and regions, makes folk art of the people. In his essay in the Everyday Art Australian Folk Art catalogue, Jim Logan writes "folk art is story-telling made material. It is, if you will, oral history in hard copy"2. This mode of translation, from stories to material objects, as well as the focus upon everyday and commonly shared events, like births, deaths, marriages and homes, makes folk a kindred spirit of family history. When data is put aside the ‘real’ sense of people and their lived experience is carried along by shared stories and materiality.

Often folk art expressions have developed from a need, the use of found or handy materials, as a reflection of one's surrounding world, and has resulted in particular and sometime peculiar outcomes. Within folk art can be seen the ways in which people, particularly in times of challenges to their survival or identity, can take collective and community shared traditions and use them, adjust them, repurpose them toward their own needs and expressions. Folk expressions are endlessly shifting, reflecting lived experiences which may be very different to iterations of those traditions from centuries earlier.

Australian folk expressions, particularly those from settler colonists and their ensuing families, developed their own flavour with their origins in a simultaneous longing for a faraway ‘home’ mixed with the grappling of how to make home upon an unfamiliar land and make use of found materials. Though European traditions have persisted in folk art expressions, perhaps a folk art of now can be redirected toward analysing some misunderstandings of this country inherited from our forebears. Instead folk expressions of now could be used to finally see interconnected ecologies, communities and local species with the care and respect they deserve.

1. Jeff McMillan, ‘The House That Jack Built: Essay as Sampler’ in British Folk Art, TATE Britain, London, 2014, p. 12.

2. Jim Logan, ‘Towards a definition of Australian folk art’, in Everyday Art Australian Folk Art, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1998, p. 4.

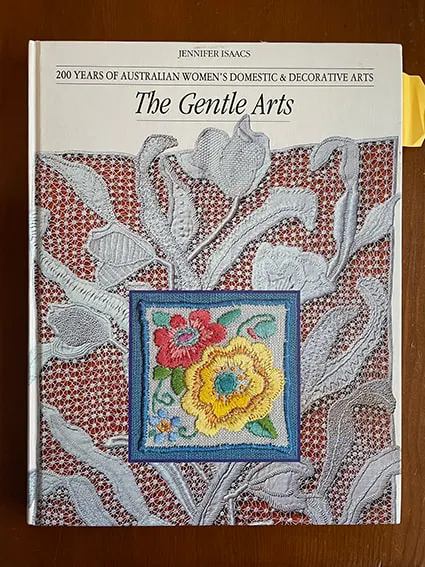

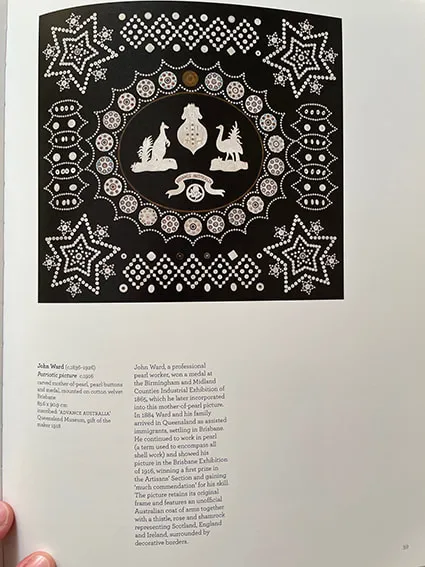

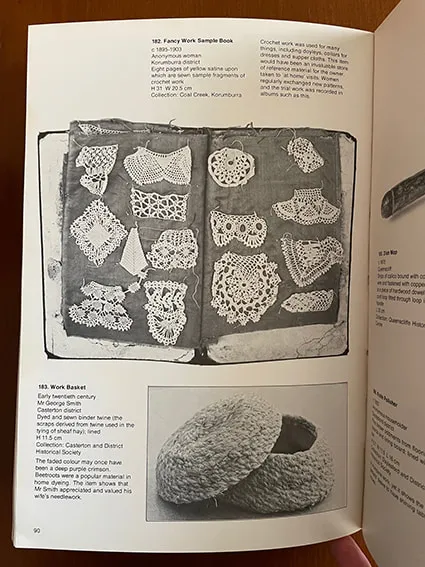

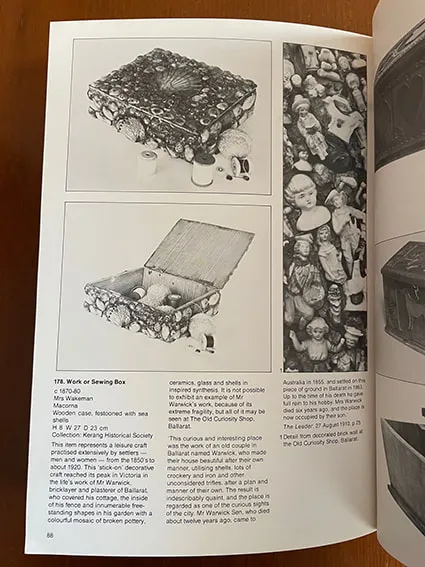

Examples of early settler colonial folk art

Excerpt from: Michael Beckmann, Judith McKay, Glenn Cooke, ‘Folk art in Queensland’ in Queensland Folk Art exhibition catalogue, Ipswich Art Gallery, 2009, curators: Michael Beckmann, Judith McKay, Glenn Cooke, p. 13

"Among the popular 19th-century needlework techniques were patchwork, knitting, crochet and Berlin wool work. Patchwork, making thrifty use of left-over scraps of fabric, was applauded by Mrs Rawson who encouraged women to take up its most decorative form, ‘crazy work’, which is richly ornamented with embroidery. … Needlework was only one of many handcrafts used by pioneer women to ornament their homes. Other popular crafts included feather work, shell work, spatterie work, pokerwork, decoupage, macrame, rug and mat making, and decorative painting – the latter including the uniquely Australian form of gumleaf painting. Some of these crafts drew on local flora and fauna while others made use of recycled materials. Feathers were collected from native birds and poultry; gumnuts and pinecones were gathered from the bush; shells and corals were found on beach holidays; pictures were cut out of old journals; and old clothes and bags were saved for recycling – the possibilities for improvised artistry were endless".

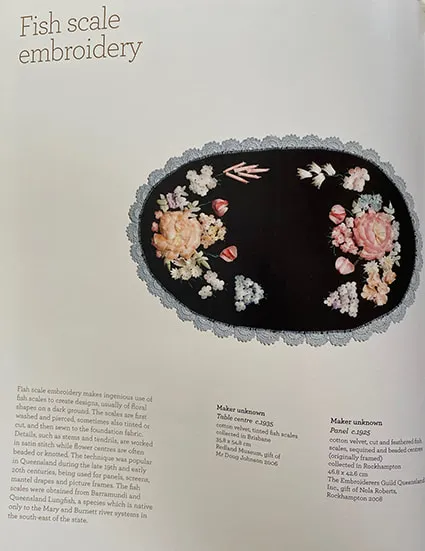

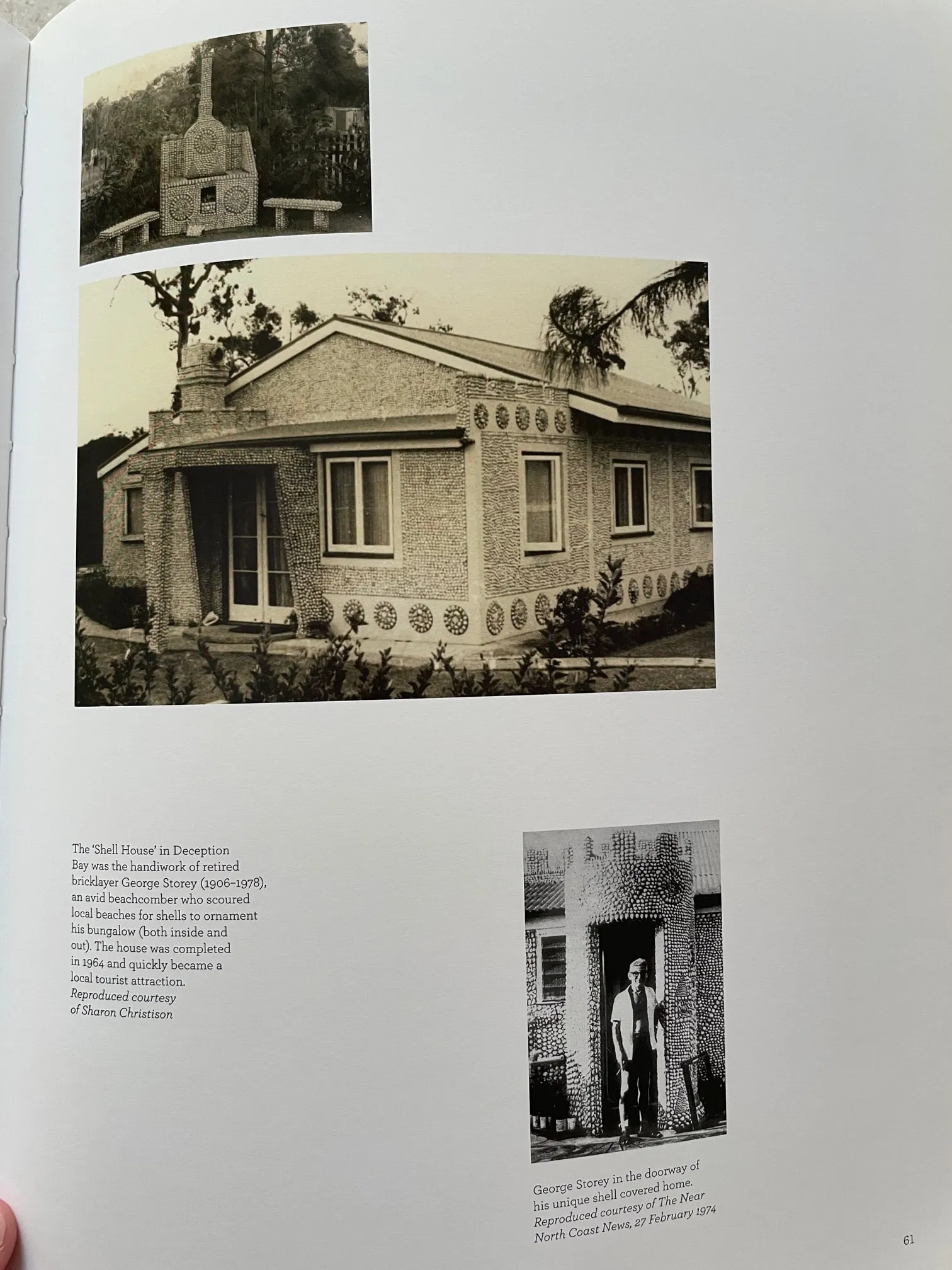

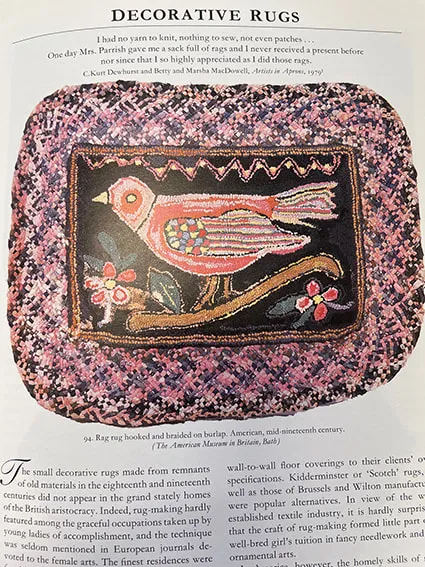

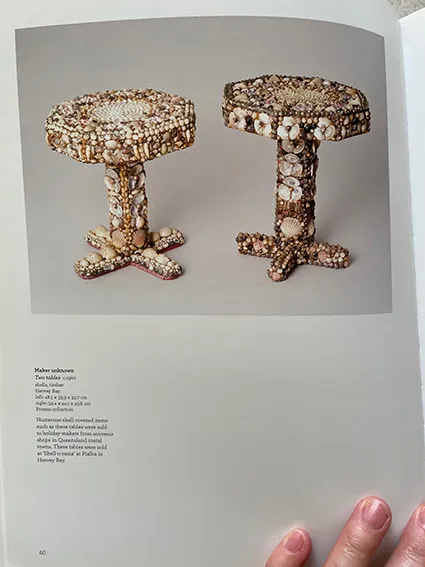

Photographs of pages from ‘Folk art in Queensland’ in Queensland Folk Art exhibition catalogue, Ipswich Art Gallery, 2009, curators: Michael Beckmann, Judith McKay, Glenn Cooke. From top left: John Ward, Patriotic Picture, c. 1916, carved mother of pearl buttons; George Storey with his 'shell house'; Two shell tables, c. 1960; Fish scale embroidery (maker unknown), an example of rag rug and braided rug on burlap.

A challenge to the decline of folk art

Many publications and experts on folk art offer a quasi-end date to this expression, claiming it has come to an end. Jeff McMillan offers the ‘mid-seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century – an end date that reflects the period before folk art arguable became a commodity or too self-conscious’1. Jim Logan too writes ‘in general folk art production ... shrank from significant production with the introduction of television. People no longer choose to fashion items for the home in their leisure hours, mass-media culture and the economics of consumerism have commandeered our attention’.2 We could also add the growing post-war prosperity which allowed families to buy consumer goods rather than have to make-do. While the uprising of kits, mass-produced home décor and more has certainly taken an emphasis away from the handcrafted, perhaps as we navigate pandemics, times of restricted supplies, an economic downturn and growing climate disasters which are causing many to seek less impactful ways of living, this end date will seem more of a pause, a temporary slowing down, before being taken up again. Of course there are places, and these are often rural places, where the inventiveness using old traditions has never ceased. These people are the knowledge holders of traditions needed for our future.

1. Jeff McMillan, ‘The House That Jack Built: Essay as Sampler’ in British Folk Art, TATE Britain, London, 2014, p. 12.

2. Jim Logan, ‘Towards a definition of Australian folk art’, in Everyday Art Australian Folk Art, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1998, p. 5.