Conductor-ors & Shields

Textiles have long been used throughout private and public worlds to direct spatial and bodily relationships, to shield, and to convey modes and codes of conduct. They oscillate between protection and control.

How can we redirect these textile traditions toward a future where spaces offer human and non-human bodies protection and care?

Photograph by Sia Duff

Courtesy of Guildhouse

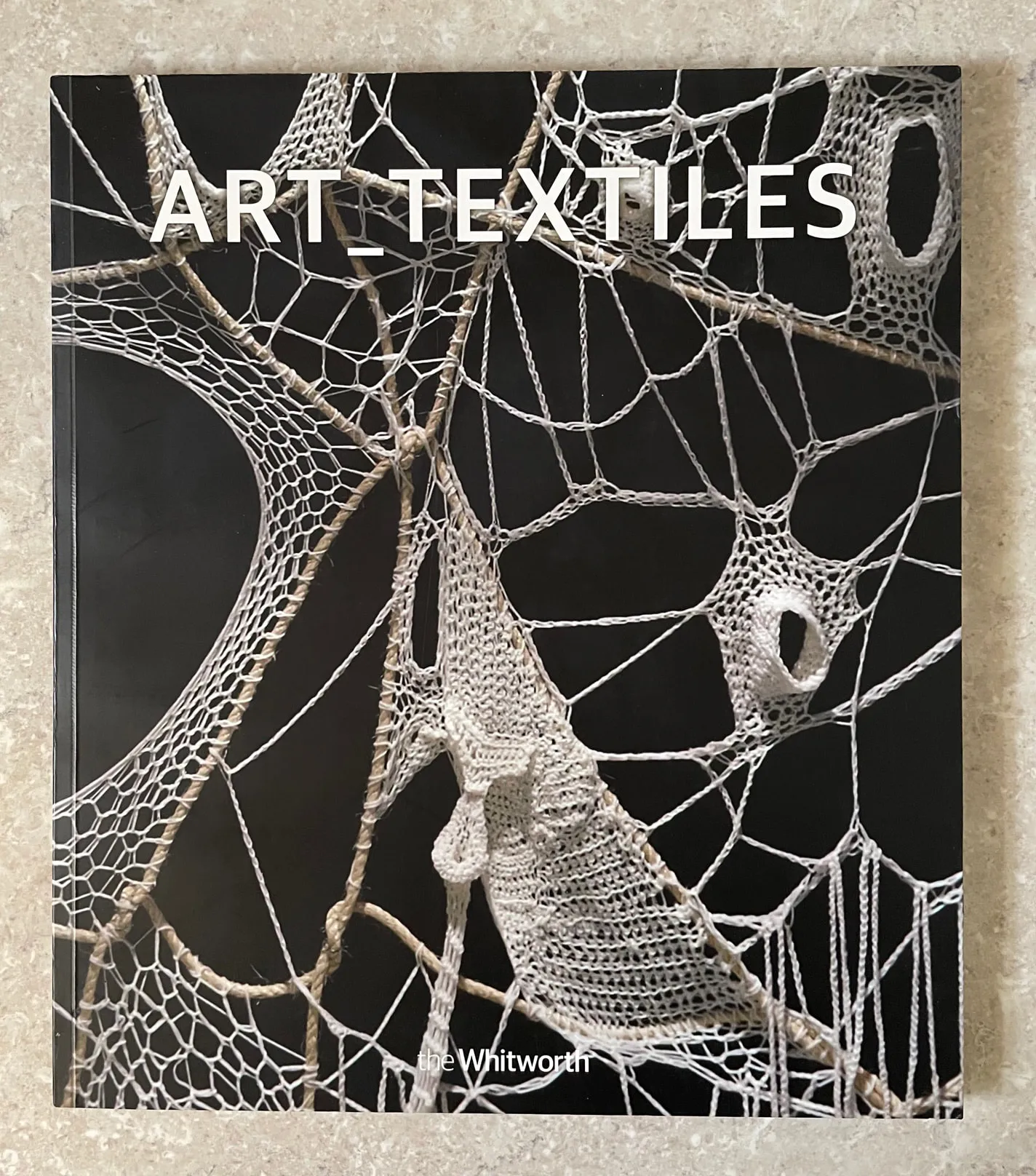

‘… [textiles] distinguish between spaces and help create the codes by which we live and work’

Julia Bryan-Wilson, ‘Living Room, Classroom, Studio, Museum: The Cultural Versatility of Textiles’, in the Art_Textiles catalogue (ed. Jennifer Harris), The Whitworth & The University of Manchester: Manchester, p. 18

Spatial demarcators, conductors and shields for bodies and homes: rugs, curtains, tablecloths, cushions, linens, hats, hoods, wallpaper, collars, clothes, pockets, chatelaine, blankets, veils, scarves, socks, handkerchiefs, doormats, bustles, flyscreens, sleeves, masks, covers, cosies, sleeping bags, pillow cases, flags, bunting, banners, tapestries, coasters/doilies, furniture protectors, lampshades, bags, string, seat covers, tea-towels, purses ...

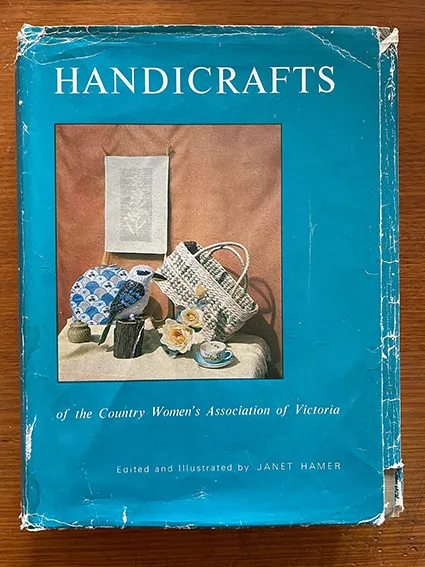

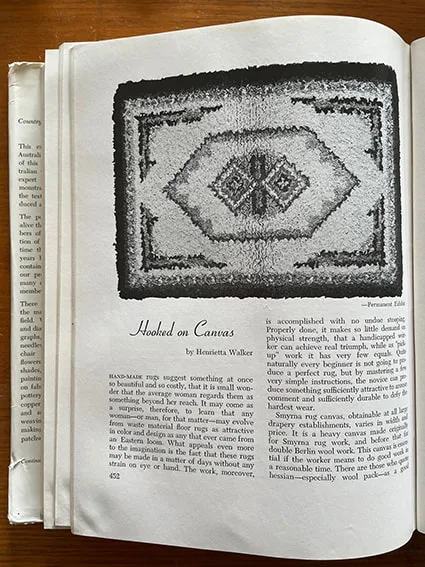

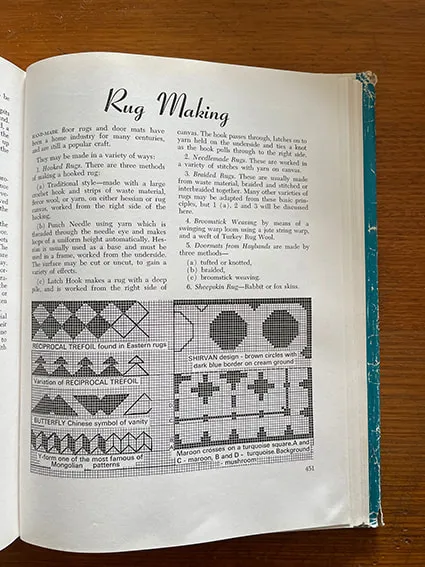

Carpets, Rugs Latch- hooking & Rag-Rugs

Carpets and rugs could be the interior's equivalent of grasslands; plush pile underfoot, a place to rest, a space of grounded softness.

“The very act of stepping on to a covered or treated surface serves to distinguish the space from its surrounding environment. …. it was accepted that flooring required careful consideration – signifying attention to detail and the all-important control of space.” Dianne Lawrence, Genteel Women, Manchester University Press: Manchester, pp. 85-86.

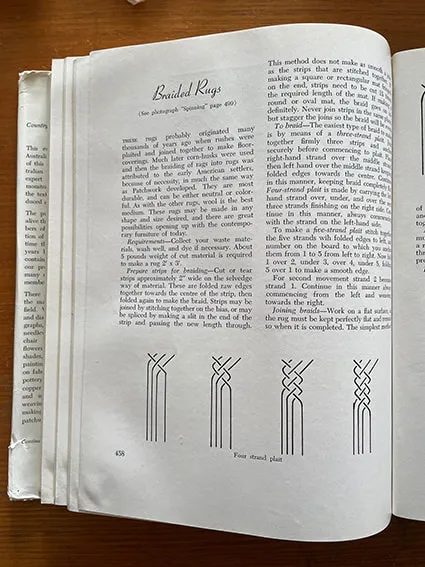

Rag-Rug Making

repurposed textiles, braided strips, torn strips, hooked strips, a rug method born of poverty, grain sack backing

Latch-hooking:

plush pile, Australiana kits, found pre-cut yarn, wool cut to lengths, shag pile, my Great-great-Grandmother's craft of choice

Many commercially designed latch-hook kits flooded the market from the 1930s and their popularity grew after World War II, especially with convalescing soldiers.

The hand latch-hook tool was invented in the 1920s, based upon the mechanism of carpet making machines. A rare example of a machined process spawning a hand-made response.

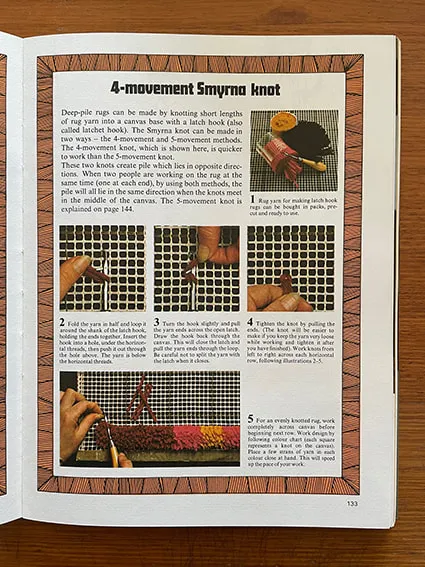

One method of latch-hooking consists of Smyrna knots, side by side, a building up of wooliness into a plush pile. The name 'Smyrna' comes from the Turkish city of Izmir, a once hub of carpet manufacturing that coincided with the time Australia was being colonised by settlers importing carpets.

Rag-rugs are thought to date back to the Vikings. With textiles being one of the main pollutants contemporarily, the repurposing of fabrics into rugs and wall-hangings (horizontal and vertical insulation and comforts) is promising as a caring tradition to carry forth into the future.

This braided rug was made under the tutelage of artist Ilka White.

HOLD

FOLD

PIERCE

PUSH

TWIST

HOOK

PULL

RELEASE

TIGHTEN

REPEAT

Artefacts

Photographs of items in the Migration Museum Collection (Adelaide South Australia): with thanks to Corinne Ball.

Photographs of items in the Art Gallery of South Australia collection: with thanks to Rebecca Evans.

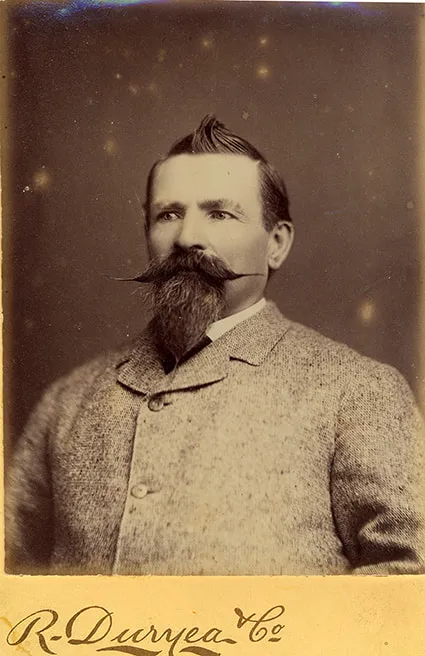

Settler Colonial Shields: A family tale from Pt Misery

Mary McKay was my ancestor who arrived in Port Misery (Port Adelaide) in 1838. She was home-maker, maintainer and gatekeeper of her family’s enclosed space. As a settler colonist upon unceded Kaurna Country in the marshy industry of the Port, she guarded the boundaries of her home against, in the words of Susan Stewart, ‘trespass, contamination, and the erasure of materiality’.1 Mary would have used many signifiers to ‘shield’ and stave off threats, which historians Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall explain ‘took practical as well as symbolic form in middle class homes and gardens and in the organisation of the immediate environment through behaviour, speech and dress.’2 This family's ‘shields’ included purporting “respectability” (through literacy, teetotalism, and attending church), domestic duties, cleaning and housework, and building a bulwark of consumer goods around them, and continuing textile traditions imported to South Australian shores in forms including linens, napery, clothing, and soft furnishings. These acted as reminders of far away homeland, and of expectations around ‘respectable’ and ‘civilised’ behaviours, which were fuelled by legacies of colonising, racist and misogynist practices. ‘Civilising’ in an Australian context equates to the passing on of European cultural practices, many ill-fitting to the land of Australia, and many of which were transmitted along female lines domestically through housekeeping and etiquette, reinforced through community groups, and embedded in the material stuff of homes.

This family tale is a reminder that textile traditions of creating 'shields' and signifiers of 'respectable' conduct were strong forces in the colonising of South Australia. Female bodies, like that of Mary, maintained and reinforced these traditions. Today, these passed along traditions are in need of being untangled, unraveled and restitched into configurations which take responsibility for the ongoing damages of settler colonisation.

1. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Durham: Duke University Press, 1993, p. 68.

2. L. Davidoff and C. Hall, cited in: Hepworth, Mike. "Privacy, Security and Respectability." In Ideal Homes? Social Change and Domestic Life, edited by Tony Chapman & Jenny Hockey. London: Routledge, 1999. P. 22.

Shields to thresholds: facial hair, talismans, lucky charms, sun protectors, bonnets, masks, fly screen, portière , milk jug cover, "respectable" attire, door mats, curtains ...

Shields as Dress: The Fox Pelt

A family photograph: Wilhelmina in the early twentieth century (c. 1900) wearing a fashionable fox fur.

Telling Tales on Terry Towelling: The Lost Flock (Foxy Ladies) (2017) takes up how fashion was used as social currency and a 'shield of respectability'. Embroidered into this towel, via a Berlin-worked lamp chop, teeth-like beads and an appliqued meaty warratah, is a sense of sacrifice and the sacrificed required for such fashionable displays; sacrifices that enable daily life, especially the laborious washing and meal routines, and sacrifices of non-human beings. Though this towel is underpinned by a heart-warming anecdote – of this sheep-farming family donating a ‘lost flock’ to help sustain their community during times of war rations – narratives of menace, predation and shields of the privileged slip through.

Extreme Barometer (2020-21) is a latch-hook rug resembling a fox pelt. It uses all second-hand and repurposed wool in the brightly alarming patterns of Australia's heat maps. Beyond the hottest magenta is the unknown and central abyss of black. This is both inviting in its tactility, an invitation in, while also cloying in its overbearing offer of heat.

This rug, hanging as a proud/shameful shield, explicates a settler colonial knot: the introduction of foxes for hunting and fashion (and fashionable hunting), the unfathomable damage inflicted by this species upon Australia's native species and the vast changes that have happened through climate shifts. A fox pelt is ironically rather too warm in this environment.